Serving the Good Life

Questioning the Ethics of Prison Architecture and Punishment:

author

personal research

national university of singapore

“How far apart should those ceiling shackles be? What dimensions did you want for that waterboard? And of course, I think it all looks best in black.” 1

- Raphael Sperry

A man must have a code no doubt. In the world of medicine, the fundamental ethical precept states that doctors first do no harm. The statement goes “I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant”2 The same applies to all professions. Lawyers have an ethics code, Journalists have an ethics code, it shouldn’t surprise that Architects do as well. The relevant ethical standard in question from the American Institute of Architects (AIA) is the recently attested ethical standard regarding Human Rights under Rule 1.402 reads ‘Members should uphold human rights in all their professional endeavors.’3 Should architects design for torture?

Raphael Sperry, president of Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) believes so too. In the wake of the Senate’s Report4 in 2012 which details acts of torture in Guantanamo Bay, the discussion of the involvement of architects regarding design for prisons were brought about in the light of Sperry’s pursuit to prevent the involvement of architects that facilitate the practice of torture. Participating in designing spaces with its intention to harm, torture, humiliate or degrade a person is fundamentally incompatible with the professional practice that represents standards of decency and human rights. It brings about the question to whether the same people who are designing our homes and everyday spaces should be the ones who are involved designing confinement spaces for mental and physical torture. It is so unequivocally in line with the image that an architect is just a shaper of society, a creative citizen serving both client and public.5

While architects cannot be held responsible for the unintended uses of the spaces that they design, the intention of most of these spaces are clear from the get-go. Confinement boxes, individualized cellular “recreation yards”, architectural features that enable and deepen isolation leading inexorably to psychological pain.6 It goes inherently behind the idea that as people of conscience and as a profession dedicated to improving the built environment for all people, we cannot participate in the design of spaces that violate human life and dignity.

The design of Pelican Bay State Prison (PBSP) by San Francisco-based KMD Architects, sparked a debate7 on designing ‘unavoidable’ programmatic prison spaces for contained programmes such as execution chambers for supermax prisons. Architects have to provide architecture for systemised solitary confinement. Should the architects involved in its design have refused the commission? Sperry no doubt would have argued that they should have, but in reality, things are far from this clear-cut. This subject is a complex proverbial minefield when it comes to the decision-making process of individual professionals.

On the other side of the coin, a new pedagogy for prisons have emerged in cases such as the Halden Prison8 and Bastøy Prison9 in Norway and Lo Wu Correctional Institution10 in Hong Kong, in which the characteristics for the prisons such as Pelican Bay Prison have been seemingly flipped and at times difficult to distinguish between jail and hotel or jail and luxurious living.

For the benefit of the essay, and to understand the ethical debate which lies between the different approaches to both maximum-security prisons: Pelican Bay Prison by KMD Architects and the Halden Prison, by Erik Moller and HLM architects. One needs to have an understanding of the evolution of discipline and punishment and the way both prisons approach this.

Evolution of Discipline and Punishment

Imprisonment started out to serve numerous social-control functions. To understand why imprisonment in the first place, one must understand the background of prisons and that prisons was never synonymous to punishment. In fact, in his book Discipline and Punishment: The Birth of the Prison11, Michel Foucault stresses that the focus in nature of shifts in prisons represented the first step away from the excessive force of the sovereign, towards a more generalized, humanitarian and controlled means of punishment. However, Foucault stresses that this shift wasn’t purely because of that, nor was it exactly to punish or rehabilitate, but as part of a continuing trajectory of subjection.

One of the oldest and most basic justifications for punishment, as early as the 17th Century, involves the principles of revenge and retribution. This equation of punishment is formed around the principle of lex talionis “An eye for an eye.” The focus of which was not about preventing future wrongdoing but simply giving wrongdoers what they deserve. Punishment as early as the 16th and 17th century came in the form of public shaming that included the pillory, acts of whipping and even the death penalty12. As argued by Foucault, it stresses the public spectacle of torture and execution as a theatrical forum which eventually reinforces “a certain mechanism of power”13. This theory, often referred to as deterrence, claims that the primary purpose of punishment is to be so harsh and terrifying that they deter people from committing crimes out of fear of being punished.

Though the ideas pertaining to public execution and torture had petted out with increasing resistance to public torture and shaming, incarceration continued to remain harsh. The means of punishment shifted towards a more “gentle” approach to criminals, though not for humanitarian reasons. The means of punishment shifted towards a thousand “mini-theatres” where convicts would be put on display through work that reflected their crime, thus repaying society for their infractions through harsh manual labour14 15.

Up till this point, prisons were not yet imaginable as a penalty. The emergence of prisons as a form of punishment only grew out as a result of the development of discipline in the 19th Century. This system continues up till today. Through observation, judgement and examination, discipline became key instruments of power and by these processes, the notion of the norm developed. The figure of the Panopticon by Jeremy Bentham16 exemplifies the idea of control through discipline. As articulated by William Bogard, the concept of the design allows for “Surveillance... [which], we are told, is discreet, unobtrusive, camouflaged, unverifiable – all elements of artifice designed into an architectural arrangement of spaces to produce real effects of discipline.”17 Punishment in the 19th Century has crossed the line from physical punishment to invade the mental capacities of inmates. Bentham himself describes this idea as “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind.”

Designing Spaces of Torture?

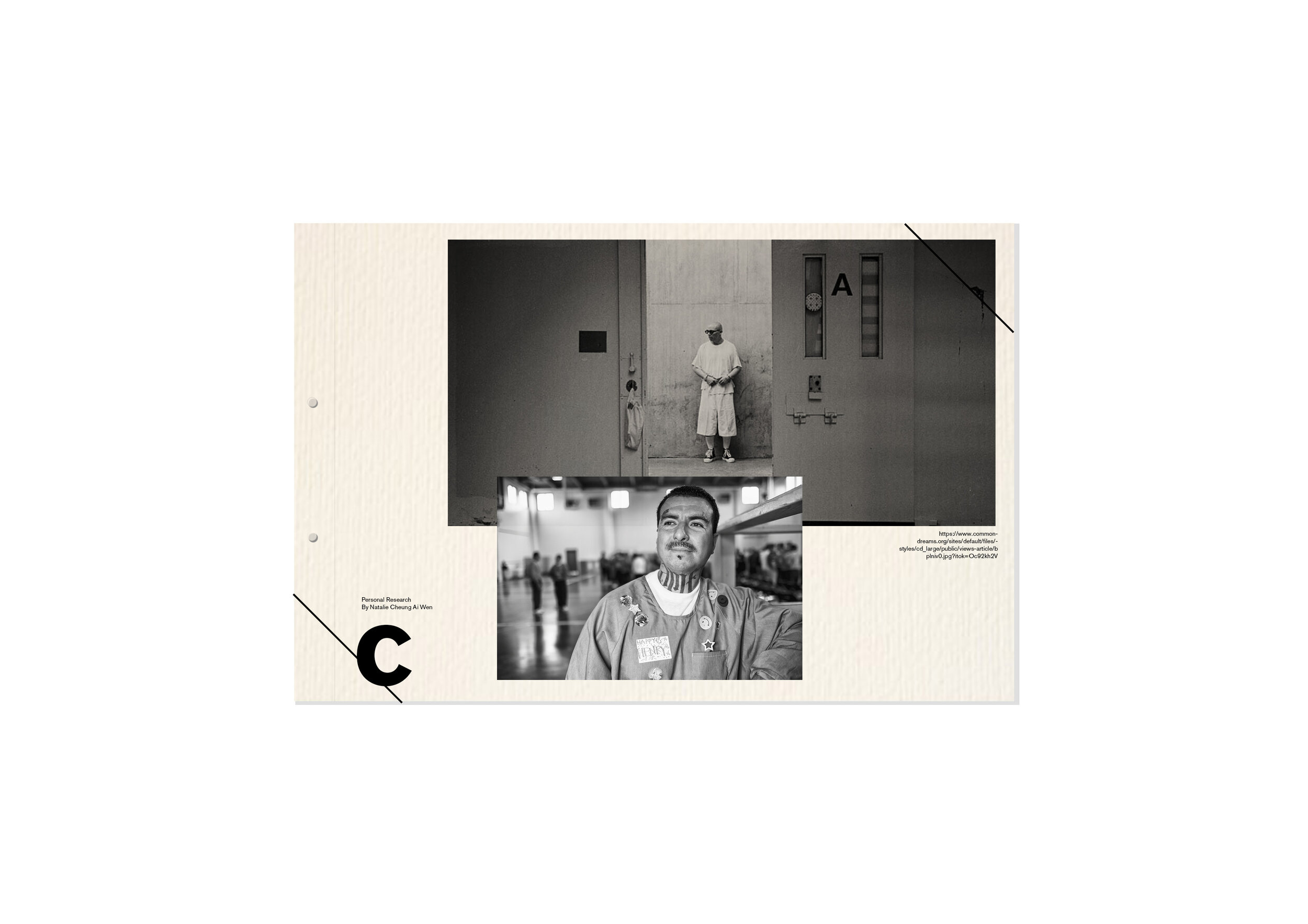

Though The Criminal Justice Act 194818 abolishes penal servitude, hard labour and flogging. Prisons as the centre of a system started to use its form to inflict pain beyond the physical, taking many different forms including remand centres, detention centres and borstal institutions. Pelican Bay State Prison is an example of how ideas of traditional and conventional forms of imprisonment still exist in the form of spaces that were designed by architects ourselves – to torture.

19 Figure 1: Birds eye view of Pelican Bay State Prison

Pelican Bay Prison - Cell Treatment

Equipped with 1,056 cells20 explicitly designed to keep California’s alleged “worst of the worst”21 prisoners, inmates are kept in long-term solitary confinement, under conditions of extreme sensory deprivation. The 8 x 10-foot soundproof cells of the Pelican Bay Secure Housing Units (SHU), are made of smooth, poured concrete, no windows and fluorescent lights that remain on for 24 hours per day. For at least, 22 hours a day, prisoners are kept in confinement within their cells that is protected by a perforated steel door that bars a solid concrete wall22.

Pelican Bay Prison - Leisure Time

One at a time, prisoners are given the opportunity to have a ‘leisure’ walk or exercise, one at a time. This exercise is allowed within a yard is built within a higher cement wall, often called a “dog run”. The yard is a length of three cells which opens up to a roof partially open to the sky. Like Bentham’s idea of the Panopticon, the guard has a central vantage point over the cement yard and can shoot into any one of six pods, each containing eight cells23.

24 Figure 2a (left): An inmate’s cell in Pelican Bay State Prison

25 Figure 2b (right): ‘Open’ yard for leisure time in Pelican Bay State Prison

Psychiatrists and psychologists have documented an “SHU Syndrome”26 that might include hallucinations, depression, anxiety, anger and suicide and that’s not surprising from the dehumanizing climate springing from KMD’s design. Though the dehumanizing context of solitary confinement can be argued from the context of time, where solitary confinement for more than 15 days should be a subject of absolute prohibition27. Architecture should be an indispensable tool in the elimination of blind spots where opportunities for violence can hide and the effort to prevent violence and torture lacks in the design of Pelican Bay. For now, Pelican Bay still resides in the 18th Century ideals of torture and deterrence, of the prison as an object of a spectacle. David Garland and Richard Sparks criticizes Pelican Bay as one that has “not been designed as a factory of discipline, or disciplined labour. It was designed as the factory of exclusion and of people habituated to their status of the excluded.”28 According to California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), there is little evidence that this pedagogy of prison architecture has any impact at all on violence levels, either with high-security prisons or within the Department overall.

2,239 prisoners29 remain housed in the Pelican Bay SHU as of March 2016. Pelican Bay Prison is just the tip of the iceberg as it stands as one of the 21 new prisons built in California in the 1980s and 1990s30.

In opposition to such the Orwellian uses of architecture, issues have been raised for American Institute of Architects (AIA) to update its code of ethics to ban architects from repeating the case of Pelican Bay. The movement towards a more rehabilitative approach towards architecture started to suffice in retaliation of the presence of architects designing spaces of torture.

Serving the Good Life

“I’ll have both, please.”, is the motto for the Halden Prison Architecture competition. Based on efforts to incorporate contrasting ideologies rehabilitative prison spurred architects Erik Moller and HLM Architects to design a new pedagogy.

Similar to Pelican Bay, Halden Prison functions as a maximum high-security, housing approximately 25032 of Norway’s toughest criminals – murderers, terrorists, rapists, sex offenders and child molesters, albeit in a different form. Unlike its labyrinthine American Supermax Prison models, there is a lack in the presence of conventional security devices like barbed wire on top of electrical fences, towers or snipers. It seems almost impossible that this new pedagogy of prison structure could be successful in housing criminals at all, not to mention, the most dangerous.

The design intent aimed at a simulation of the world outside created with the focus on rehabilitation and the hope of preparing its inmates of reintegrating into society easily. Ideas of isolation were prevented and the focus on rehabilitation of prisoners reflected in the plan, interior design, and external landscaping.

33 Figure 4a (left): Inmates private Cell in Halden Prison

34 Figure 4b (right): Inmates private en-suite bathroom in Halden Prison

Halden Prison - Cell Treatment

Though simple, the interior furnishings are modern and living. Inmates are allocated private cells which are 10 square metres35, usually bigger than the average university dorm, not to mention the suffocating conditions of Pelican Bay Cells. Each cell is fully furnished with a flat-screened television, mini-fridge and even a private en-suite bathroom with ceramic tiles and unbarred vertical windows that let in more light. Bars are replaced with doors to reflect a normal residential setting. Every 10-12 cells, prisoners share a kitchen and common lounge areas that are complete with sofas and coffee tables. While the prison provides food, the prisoners can also buy their own ingredients to make their own meal, while prison guards help to clean up.

With the intention of a variety-filled imprisonment, each building within the compound is individualized to suit its function, using materials that relate to its surroundings and to project a level of security. Even which, a ‘hard’ material that symbolises detention is made out of brick and galvanized steel and a ‘soft’ material such as larch stand for rehabilitation and growth.36

Hadlen Prison - Leisure Time

Between recreation facilities such as the ‘activities house’ – offers forest jogging trails, soccer

fields, woodshop, cooking and music classes, ‘mixing studio’, ‘cultural centre’- a sports hall with a rock climbing wall and a space to cater to large in-house events, ‘ a library’, are 20 unique yard space designs, interconnected by a ring road that connects and allows for an experience through the 75-acre open courtyard that creates a link between functions and serves as a rehabilitation process for the inmates.

“Nature is actively involved as a socially rehabilitative factor in the architecture.. the opportunity to follow seasonal changes helps to clarify the passage of time for the inmates.” 37 Between each of these individual functions are 20 different yard space designs sprinkled with million dollar art pieces by Norwegian Artist- Dolk, each of these individual functions are sited in a building of its own on a hilly wooden plot, interconnected by a one-way ring road that connects and allows for an experience through the changeable forest stand that creates a link between individual functions and a rehabilitation process for the inmates. Prisoners are allowed the right to house their visitors overnight in segregated chalet-like units that are made less institutional in order to give family and children and opportunity to be together in as natural an environment as possible.

Figure 5a (left): Jogging Trail within Halden Prison boundaries

Figure 5b (right): Rock Climbing Wall for Inmates

Figure 6a (left): Supermarket for Inmates

Figure 6b (right): Dolk Art found around Halden Prison Walls

The list of benefits goes on and on. “This is prison utopia,” a retired warden from New York, James Conway said in a documentary about his trip. “I don’t think you can go any more liberal — other than giving the inmates the key”38

The only obvious symbol of incarceration is the 20-foot concrete security wall along the prison’s 75-acre facility perimeter, even which its image as “symbol and instrument of punishment” is softened by trees which obscure the view of it and a rounded top, to avoid a hostile environment. Hallways are decorated with Moroccan tiles and large-scale photographs and paintings. Yard walls and toilet doors are decorated with $1 million budget for Norwegian Artist, Dolk’s Art. Though there is safety glass, a system of underground tunnels for guards and a 6m by 1.5km tall concrete and steel wall, surveillance is not present in facilities other than the outdoor prison grounds.

In effect, this Norwegian Penal System boasts one of the world’s lowest recidivism rate of 20%39. No one in the prison has attempted to leave yet and I am not surprised. By prioritizing the human rights of its inmates, “doing time” is done in a dignified way, bordering on luxurious, provided for criminals such as the notorious Anders Behring Breivik, the perpetrator of the deadliest recorded rampage which killed more than 77 people and injured hundreds more in 2011. Since then, Brevik, who was held during his trial at the Lla Prison, a former Nazi Concentration camp, has taken to protesting the ‘deprivations’ of his incarceration40 – including, poor access to video games – and making daily demands for more walks and monetary allowance and fewer body searches. Alan Weston, currently serving his second rape sentence at HMP Frankland, complained to prison newspaper Inside Time this month saying he couldn’t access National Prison Radio (NPR) on his new digital system41. An increase in foreign convicts wanting to enter Norway’s prison increased from 8.6 percent in 2000 to 34.2 percent in 201442 due to its reputation as ‘cushy’ form of punishment. Whether this proves Hannah Arendt’s point, writing of the Eichmann trial, ”on the banality of evil”43, or the tormenting efficacy of a reward system built on the foundation of large and small daily humiliations, remains to be seen.

While Halden proves the new pedagogy of prison architecture, its characteristics call to mind the all-inclusive holiday paradise - ClubMed – you could be forgiven for doubting Halden as a prison at all. While the first scene of Breivik’s crimes, remains in suspended animation, still scarred by the July 2011 bombing44. Looking back at the emergence of prisons, is its purpose not meant to stage a theatre of cautionary tales that shame, entertain, warn or deter any future wrong-do-ers? If prisons do not possess characteristics of deterrence or a certain level of deprivation of freedom, should we still call it a prison? While Norway defines punishment as a deprivation of freedom, the only deprivation of freedom taken away is the inability to leave the large beautifully landscaped boundaries of Halden, while being occupied by over the top facilities. It is, ironic that the quality of life in prison is said to be better than in many nursing and retirement homes. In a special case, would there not be a criminal who would then commit a crime to re-enter this “heavenly prison” should the environment outside prove to be harsher. This prison environment attracts rather than deters. It offends a certain sense of justice we have sought throughout the years. The answer is not to revert back to the traditional conservatism approach. Though I do think the severity of punishment does help to deter. What the Norwegian system does for us is to prove that, rather than conceding to violence and squalor as the inevitable conditions of our penal system, putting the $50,00045 California spends a year per prisoner towards treating them as a human being is a notion very much exploring.

The question here is, how comfortable should punishment be?

Comfortable punishment is an oxymoron yet designing luxuriously in excess cannot justify our claims for prisons as a form of punishment. ‘It was your actions that put yourself here,’ Conway says ‘Who cares how they feel?’46. The understanding of the aim of a prison should not be to hurt people who have hurt others as we have moved on from ideas of the conservative, it is to make it so inmates do not have an innate incentive to hurt again, as Halden Prison has done although in excess. Torture, pain, and hard labour inspire a population to go against rather than discourage. Whereas, the more humane and seemingly successful way to prevent re offence by criminals is a facility like Halden, that treats prisoners as human beings and work to address the reasons they offended in the first place. This is a fundamental idea that should be prioritized: Human rights and sufficient living conditions – suitable temperature, views to nature and a reasonable amount of walking space.

We look again at the fundamental principles of prison design that Halden is complacent with – the idea of control and prison as a deterrence. In return, is comfortable rehabilitation really a replacement for punishment? Halden Prison barely enforces the idea of the deprivation of freedom, but is that punishment justified enough?

A few examples architects could consider is the subtle play on the idea of rehabilitation while controlling inmates not through force but subtleties such as colours on typically hostile concrete walls, or the fixing down of furniture. Architecture as a whole has the ability to influence people both intentionally and unintentionally. Just as bad architecture has the ability to evoke a sense of dissatisfaction amongst people, good architecture has the ability to change behavior and create spaces which are suitable to the need; but suitable architecture is the one which defines what is necessary to the use, and that is what prisons should aim for, an architecture which encourages the rehabilitation of prisoners instead of isolating them from society, but at the same time remain a physical and environmental consequence for the crimes which they have done. If anything, one should not hide away the walls which imprison, but maybe let them sit silently as architecture that quietly contains.

“If architects won’t design it, who would?”